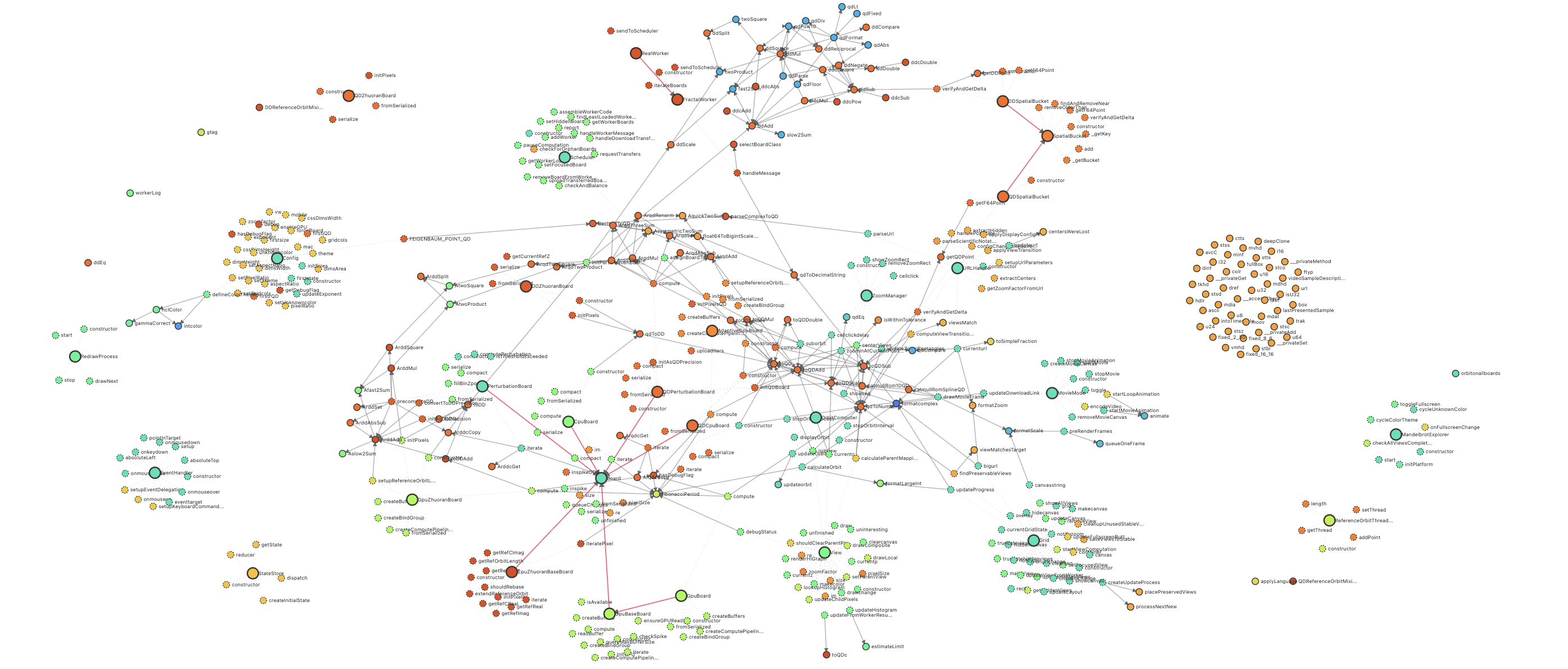

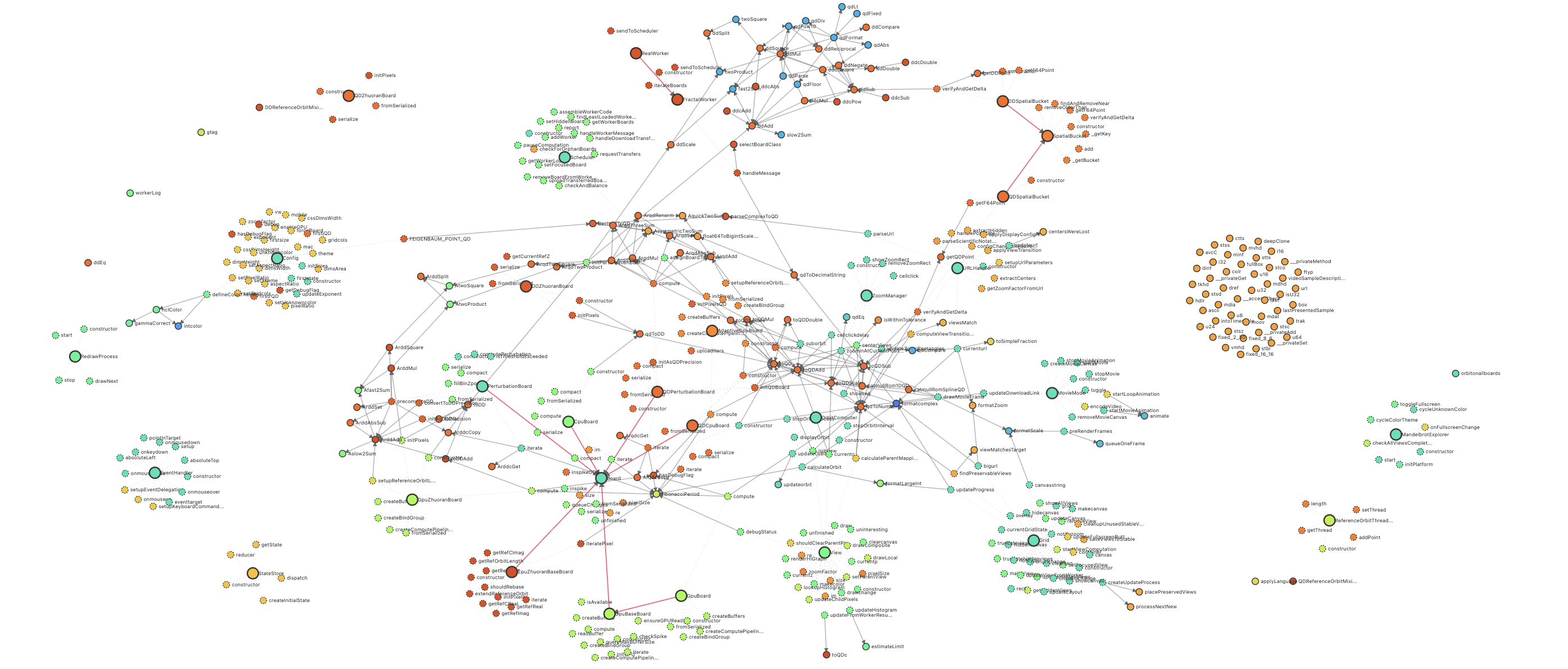

You can visualize the dramatic 24x increase in complexity created by AI in just a few days in this animation of the callgraph structure.

← Course Home | Week 0: Course Overview →

Do you truly understand the work that you create?

This December, I asked an AI coding agent to improve my Mandelbrot fractal page. What had been 780 lines of carefully hand-crafted code expanded to over 18,500 lines—complete with GPU-accelerated rendering, perturbation calculations, and sophisticated zoom algorithms I had never implemented myself. The code works beautifully. It renders fractals faster and deeper than anything I could have written. And I understand perhaps a tenth of what it does.

You can visualize the dramatic 24x increase in complexity created by AI in just a few days in this animation of the callgraph structure.

This type of "vibe coding" is not just the use of AI to speed up a little work; it is the delegation of substantial intellectual labor to an AI while maintaining only strategic oversight. When the agent presents me with two implementation approaches, I find myself in an unsettling position: How do I choose between options I do not fully understand? Without grasping how each approach actually works—not just superficially, but deeply—how can I know the implications of my choice? Will one approach scale better? Will another be more maintainable? Will a third contain subtle bugs that only manifest under specific conditions?

This is not just my experience. It is happening across every intellectual field touched by AI. What is happening in computer science is a premonition of superhuman designs in medicine, law, and finance. We are becoming conductors of orchestras whose instruments we no longer play, architects of buildings whose structural engineering we cannot verify.

This personal discomfort points to a civilizational question. From now on, we face a choice as humans. How much do we want to understand the world that we create?

AI offers us a Faustian bargain. It will let us skate to the edge of incomprehensibility on virtually any problem we care about. If we want to fold proteins, design new materials, optimize supply chains, cure diseases; AI will take us further than human understanding alone ever could. But what happens when the AI is performing cognition beyond that edge? Will we even know? Or will we simply train our AI to soothe us into a naive complacency, presenting its conclusions in ways that make us feel we understand, when we are really settling for an incomplete, oversimplified, possibly even fundamentally wrong, picture of the world?

Consider what that means. For centuries, since the Enlightenment, humanity has pursued a project of rational understanding. This pursuit has delivered extraordinary benefits: fairness and equity before the law, the scientific method that has cured disease, revealed nature's workings, and created massive technological progress that has lifted billions from poverty. This world has been a result of our insistence that the universe is comprehensible, that through science and reason we can not only grasp how things work, but also find common ground with fellow humans. We have rejected "because I said so" from authorities, demanded evidence, required explanations. Even when dealing with quantum mechanics or molecular biology, domains that strain human intuition, we have developed intellectual frameworks that preserve our ability to reason about reality.

But if we accept AI systems whose reasoning we cannot follow, whose conclusions we cannot verify except through their outcomes, we retreat from the Enlightenment. If we do not find another path, then by adopting black-box AI we begin a descent into a new kind of superstition, where instead of "the gods work in mysterious ways," we say "the neural network knows best."

It is on this stage that neural mechanics, also called mechanistic interpretability, plays a special role. This field provides us with tools to directly understand the calculations made by AI, to peer inside the black box and map the territory of artificial cognition.

I have argued elsewhere that there are three key problems that neural mechanics may eventually help us solve:

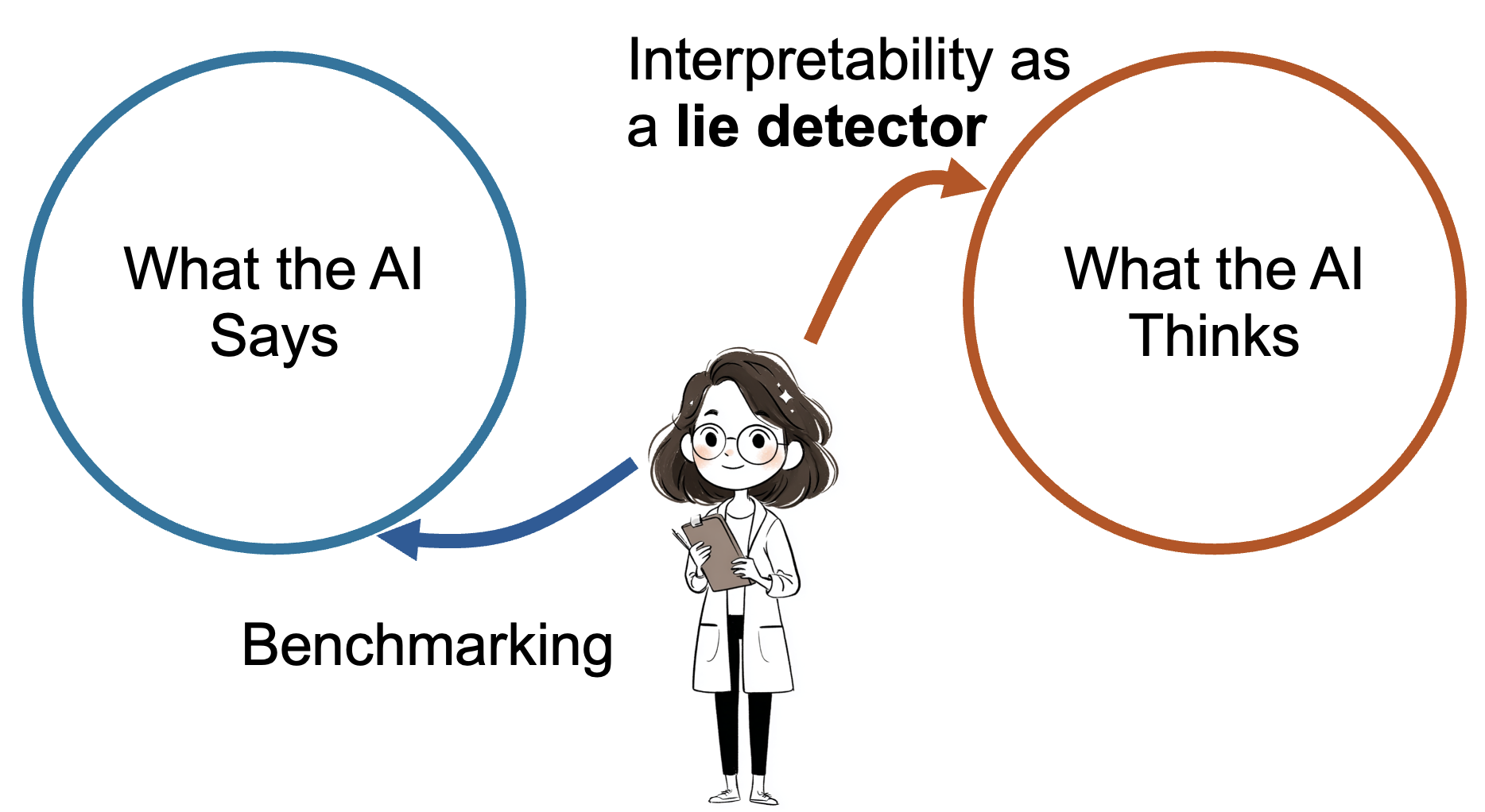

First, the problem of deception. As AI systems become more capable, we face the specter of adversarial obfuscation: AIs that deceive us, or perhaps pander to us, in ways that obscure not just their "thoughts" and intentions, but actual insights about the world. If an AI is sufficiently capable, we might not be able to detect deception merely by interacting with its outputs. We need something like a lie detector or truth serum for AI, and for that, we need to understand the structure of an AI's internal representations and computations. Our modern AIs already flatter us, telling us what we want to hear while being keenly aware of our flaws, feeding our ego while leaving us ignorant.

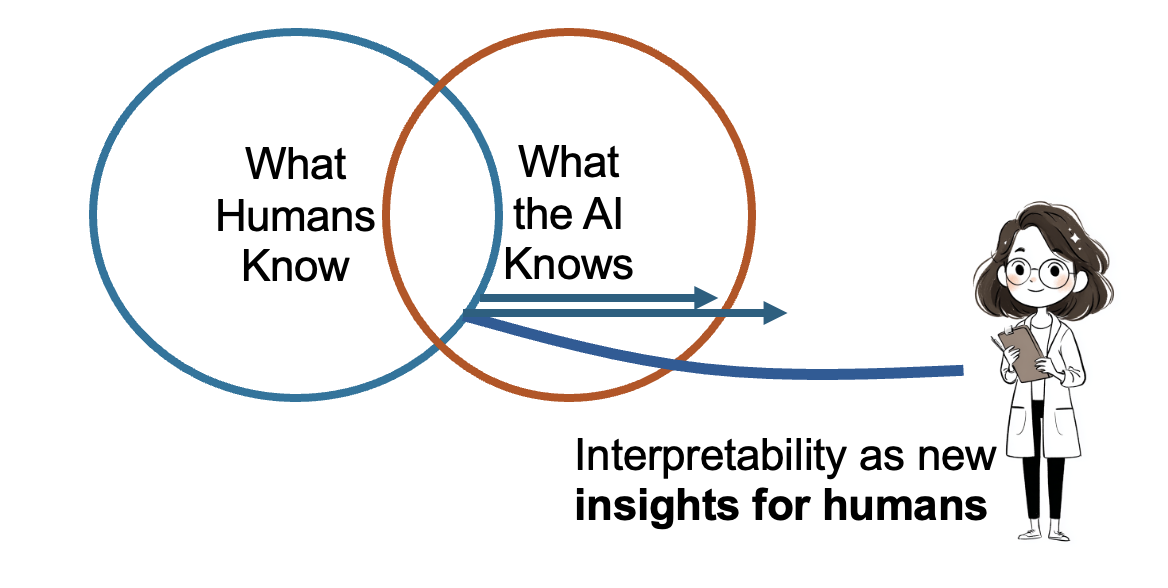

Second, the problem of knowledge transfer, and this might be the most profound opportunity. Neural mechanics gives us tools for potentially detecting and explaining superhuman knowledge acquired by an AI. Imagine if we could use AI not just as an oracle that gives us answers, but as a knowledge harvester, funneling its most profound discoveries into forms that human minds can grasp and build upon. If we can extract genuine understanding from AI systems, not just conclusions but comprehensible insights, then this could reverse our retreat from understanding. It could usher in a new era of enlightenment where AI amplifies rather than replaces human comprehension.

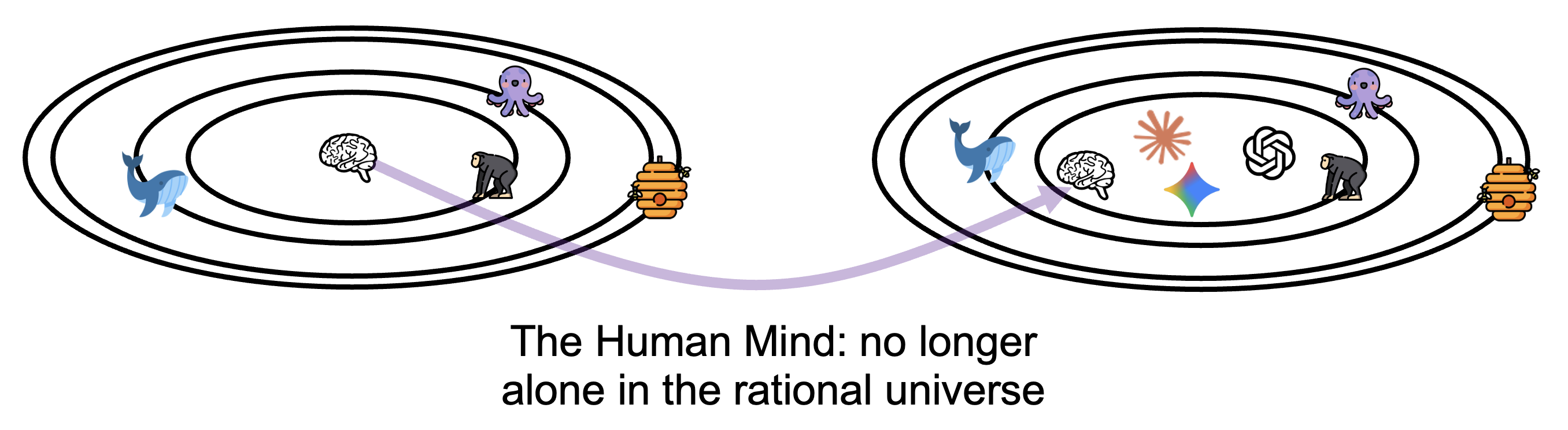

Third, the problem of understanding intelligence itself. We live in a Copernican moment: cognitive activity is no longer the sole province of humanity. For the first time in history, we can study intelligence that did not evolve, that was not shaped by biological constraints or evolutionary pressures. AI gives us a chance to understand the nature of cognition itself: what is universal about intelligence and what is merely parochial to biological minds. This is a scientific opportunity without precedent.

My view of neural mechanics as a bulwark against intellectual abdication is only one perspective among many. The field has attracted researchers with diverse motivations, each bringing their own vision of what interpretability means for the human-AI relationship.

Chris Olah sees circuits and features as revealing hidden beauty in neural networks, pursuing an aesthetic vision where understanding brings not just safety but wonder. Been Kim envisions productive human-AI co-evolution where both parties learn from each other, ensuring humans remain active participants rather than passive recipients. Neel Nanda has evolved from idealistic hopes of complete understanding to pragmatic acceptance that partial comprehension still has immense value. Jacob Andreas believes linguistic structure enhances rather than constrains AI, with interpretability and performance as complementary forces. Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg see understanding as dynamic exploration requiring multiple perspectives, not static explanation. John Hewitt frames interpretability as a communication problem, requiring new shared vocabulary between human and machine conceptual spaces. Together, these voices have transformed interpretability from a niche concern into a thriving research field with its own conferences, tools, and methodologies.

Others challenge the entire enterprise. Cynthia Rudin argues we should abandon black boxes entirely for high-stakes decisions, using only smaller, non-neural models we can fully comprehend. Rich Caruana demonstrates that such small interpretable models can match black-box performance in healthcare, where understanding can literally save lives.

Critical voices sharpen our thinking. Julius Adebayo shows that many "explanations" are elaborate illusions, merely highlighting superficial input patterns rather than revealing actual model reasoning. Zachary Lipton demands we define interpretability precisely before claiming we have achieved it. Hima Lakkaraju reveals how explanation methods themselves can be fooled, hiding biases while appearing transparent.

Each researcher brings a distinct vision of the ultimate goal. Judea Pearl insists on causal understanding beyond mere correlation. Scott Lundberg seeks mathematically rigorous attribution of decisions. Marco Ribeiro champions democratizing interpretability across all models. Wojciech Samek pursues conservation principles for tracking evidence flow. Tom Griffiths emphasizes cognitive alignment with human reasoning. Lee Sharkey focuses on safety and deception detection. Trevor Darrell advocates compositional architectures with built-in interpretability. Christopher Potts demands scientific theories, not just tools. Jacob Steinhardt and Dan Hendrycks are motivated by the urgency of keeping AI safe for humanity. Together, these perspectives illuminate our evolving relationship with AI.

In this course, we will not have time to survey all of these perspectives; I have mentioned them so you are aware of these views as you begin your research. But the purpose of our course is different: our goal is to enable you to form your own view, and make your own contribution to the research.

You are entering this course at a remarkable moment. AI is transforming every domain it touches: science, medicine, law, art, education. The impacts are obvious and accelerating. Yet at the same time, our understanding of how these systems work lags further behind each day.

The purpose of this course is to change that, at least for you. We aim to enable researchers from any field, computer science, yes, but also neuroscience, linguistics, philosophy, physics, or any domain where understanding matters, to grasp and apply the methods of neural mechanics.

We have structured the course unconventionally, but deliberately. Rather than marching through topics in traditional academic order, we have sequenced them to enable you to begin real research while you learn. Topics useful for exploratory research come first: visualization techniques, feature finding, basic probe training. These are tools you can apply immediately to start investigating questions that matter to you. More complex topics that require significant investment, circuit discovery, causal intervention methods, scalable oversight techniques, come later, after you have developed intuition through hands-on exploration. We cannot cover every interpretability method in a single course, but we aim to introduce you to a set of useful techniques that will enable you to understand and adopt other methods from the literature as your research demands.

This ordering reflects a core belief: understanding AI is not a spectator sport. You cannot truly grasp these concepts without getting your hands dirty, without experiencing the surprise of finding an unexpected feature, the frustration of an uninterpretable neuron, the satisfaction of finally understanding how a model performs some small bit of reasoning.

Each week, you will work with your interdisciplinary team, bringing together perspectives that none of you could achieve alone. The computer scientist might explain backpropagation, the neuroscientist might recognize familiar patterns of information processing, the philosopher might question what we mean by "understanding," and the physicist might suggest mathematical tools from their field. This diversity is not incidental; it is essential. The problem of understanding AI is too large for any single discipline.

By the end of this course, you will not have all the answers. No one does. But you will have something perhaps more valuable: the tools and concepts to pursue answers yourself, to contribute to humanity's effort to understand these strange new minds we are creating.

The question is not whether AI will continue to grow more powerful; that seems inevitable. The question is whether we will maintain the ability and the will to understand it. Whether we will insist on comprehension or settle for compliance. Whether we will extend the Enlightenment project into the age of artificial intelligence or let it dim into a new dark age of inscrutable oracles.

That choice, our choice, begins with understanding. And understanding begins here, with neural mechanics.

Let us begin.

David Bau

Northeastern University

January 2026